“QOZ 2.0 could rewrite the rules of engagement between capital and community—ushering in a new era of place-based investment grounded in accountability, transparency, and shared prosperity.”

— Tony Cho, Founder & CEO, Future of Cities

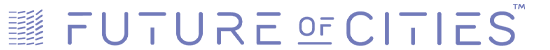

Last week, Future of Cities had the opportunity to join two dynamic convenings that are helping to shape the next chapter of equitable development: the Miami OZ Summit 2025 at the Frost Science Museum in Downtown Miami hosted by the City of Miami’s Department of Economic Innovation & Development, and the Yellow Brick Road to QOZ 2.0 summit held in Park City, Utah hosted by Greenberg Traurig LLP.

“While the original intent of Opportunity Zones was to support both real estate development and the growth of operating businesses, the current regulatory environment often makes it difficult for startups and existing businesses to thrive. QOZ 2.0 should simplify rules for business qualification to ensure that we are truly fostering local entrepreneurship and economic growth within these communities.” — Jim Lang, Shareholder, Greenberg Traurig, LLP

These two events brought together some of the top minds in Qualified Opportunity Zones & Funds — family offices, developers, policymakers and community advocates to discuss what’s working—and what’s needed—for Opportunity Zones to fulfill their promise.

The goal? To connect capital with projects that are not only profitable, but regenerative—projects that elevate communities, foster resilience, and deliver long-term social value.

Miami OZ Summit 2025

Hosted by the City of Miami’s Department of Economic Innovation & Development, the Miami OZ Summit 2025 opened with remarks from Mayor Francis X. Suarez and U.S. Secretary of Housing & Urban Development highlighting the importance of Public-Private Partnerships, setting the tone for a day centered around community-driven development & economic innovation.

On Public-Private Partnerships

“…local electives have the flexibility to understand and to make the decisions on how they want to build these neighborhoods.”

– US Secretary of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) – Scott Turner

At both events, a clear sense of alignment & agreement emerged among industry leaders, policymakers, and investors: the future of Opportunity Zones must prioritize:

- a long term extension to existing OZ zones with adjustments to the timelines and terms of the program

- innovations in bank incentives to provide more financing into OZs

- simplification of rules & restrictions for greater accessibility and flexibility to operate businesses in OZs

Across panels and presentations, there was strong consensus that these proposed policy updates would create more long-term value and an inclusive framework for investment. By centering local voices and mission-aligned capital, these changes have the potential to transform Opportunity Zones from a financial incentive into a powerful tool for regenerative development, unlocking long-term value in historically underserved neighborhoods.

“In terms of the way we zone our city, we also rely heavily on the private sector. We invite the private sector to the table as visionaries. We set the parameters, we set the rules, the limits but within those rules & limits we think that they have the best capability of visioning neighborhoods, of visioning developments & its worked really well. You were able to see and get a sense of how the city is growing and see how eclectic the neighborhoods are… it’s led to 140% growth from 2015-2024.”

– Mayor of Miami Francis X Suarez

As legislation continues to evolve, so does the understanding of what Opportunity Zones can—and should—be. From climate-resilient infrastructure to culturally-rooted placemaking, this policy could expand far beyond the multifamily model that once defined it & these conversations are only the beginning.

At Future of Cities, with our continued commitment to SDG 11 Sustainable Cities & Communities, we remain committed to reimagining what opportunity truly looks like—on the ground, in policy, and in partnership with the communities we serve.

Our Opportunity Zone Demonstration Projects

“We’ve been investing in Opportunity Zones since the very beginning—not just as developers, but as EcoSystems Thinkers. It’s not enough to build housing. We need to build ecosystems of innovation, equity, and healing.”

— Tony Cho, Founder & CEO, Future of Cities

Future of Cities’ flagship Opportunity Zone demonstration projects include:

PHOENIX ART & INNOVATION DISTRICT

The Phoenix Arts & Innovation District in Springfield, Jacksonville, which is activating local talent and culture to catalyze creative economies & small business incubation along with tackling access to affordable housing and healthy food in an urban food desert.

CLIMATE & INNOVATION HUB

The Climate & Innovation HUB in Little Haiti, Miami, a regenerative placemaking campus designed to support circular economies, innovation, climate tech, and community collaboration.

Subscribe to Regenerative Living Substack

“The magic of resilient & regenerative cities lies not just in buildings, but in the people who inhabit them. We have to move beyond transactional development to something transformational.”

— Tony Cho

Get Tony’s personal insights, policy breakdowns, and behind-the-scenes updates on regenerative living, purpose-driven leadership, and what it really takes to build the future of cities. Subscribe to the substack to receive upcoming insights & updates directly to your inbox.

As our cities and towns expand to accommodate growing populations, the balance between urban development and ecological preservation becomes increasingly fragile. One critical strategy to address this challenge is the creation and maintenance of green corridors. These continuous stretches of vegetation, connecting parks, forests, wetlands, and other natural habitats, are essential for promoting biodiversity, improving quality of life, and enhancing climate resilience.

What Are Green Corridors?

Green corridors are linear green spaces that link larger natural areas, enabling wildlife to move freely and safely across fragmented landscapes. They can take many forms: riverbanks, urban greenways, tree-lined streets, or even vegetated rooftops that connect natural habitats within cities. By integrating nature into urban and suburban environments, green corridors create pathways for ecological connectivity.

One example of green infrastructure supporting wildlife is the green bridge in Nettersheim, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, which allows animals to safely cross the Autobahn A1, reducing road fatalities and maintaining genetic flow between populations.

Ecological Benefits

One of the primary functions of green corridors is to support biodiversity. Habitat fragmentation—caused by roads, buildings, and other infrastructure—is a leading cause of species decline. Green corridors mitigate this by providing:

- Safe Passage: Animals can migrate, forage, and breed without the threats posed by traffic or human interference.

- Gene Flow: Corridors facilitate genetic exchange between wildlife populations, which is crucial for maintaining healthy ecosystems.

- Pollinator Support: Bees, butterflies, and other pollinators thrive in these connected green spaces, ensuring the health of both natural and agricultural systems.

Organizations like Wildpath, The Nature Conservancy, and Wildlife Corridors Australia are actively working to establish and protect green corridors that sustain biodiversity and ensure safe wildlife movement.

Climate Resilience

In the face of climate change, green corridors are vital for creating resilient communities. They contribute by:

- Reducing Urban Heat: Vegetation in green corridors lowers surface and air temperatures, combating the urban heat island effect.

- Carbon Sequestration: Trees and plants absorb carbon dioxide, helping to offset emissions.

- Flood Mitigation: Green corridors often include permeable surfaces and water features that absorb excess rainwater, reducing the risk of urban flooding.

An example of this is the Recreio Green Corridor Project in Brazil, launched in 2012 by the Municipal Secretariat for the Environment. This project aims to protect and enhance the biodiversity of the region while helping the west side of the city adapt to coastal flooding and erosion.

Nonprofits such as Rainforest Trust and Green Corridors (South Africa) are also focusing on reforestation and ecosystem restoration to enhance climate resilience worldwide.

Social and Economic Benefits

Beyond ecological advantages, green corridors offer significant social and economic benefits:

- Improved Health: Access to green spaces encourages physical activity, reduces stress, and improves mental well-being.

- Enhanced Aesthetics: Tree-lined streets and landscaped pathways increase property values and attract tourism.

- Community Connectivity: Green corridors double as pedestrian and cycling routes, fostering active transportation and community interaction.

Mexico City showcases both older and newer green corridor infrastructure, with shaded walking and cycling routes in the Roma and Condesa districts, and the innovative Ecoductor – Walking River, integrating walking into green and blue corridors while connecting with the city-wide cycle hire scheme.

Organizations like Urban Green Spaces (UK) and Green Infrastructure Partnership advocate for green corridors as tools for enhancing urban livability and well-being.

Challenges and Solutions

The implementation of green corridors often faces challenges such as land acquisition, funding, and competing urban priorities. However, these hurdles can be addressed with innovative approaches:

- Public-Private Partnerships: Collaboration between governments, developers, and non-profits can pool resources for green corridor projects.

- Integrated Planning: Including green corridors in urban master plans ensures they are prioritized alongside infrastructure development.

- Community Involvement: Engaging local communities in the planning and maintenance of green corridors fosters stewardship and ensures the spaces meet public needs.

Inspiring Examples

Globally, there are inspiring examples of green corridors transforming urban areas:

- Piggyback Yard Feasibility Study, Los Angeles: This project examines converting a 125-acre rail yard into a new terrain supporting riparian habitat and providing public access while maintaining hydraulic performance during peak flows within the central corridor of Los Angeles. Outlining the development and hydrological programs that will transform Piggyback Yard from a concrete industrial landscape to a “River Destination,” this ambitious vision serves as a catalyst for urban regeneration along the LA River corridor. Despite these ambitious plans, the primary obstacle remains Union Pacific’s steadfast position on retaining the property for its rail operations. This stance has made it challenging to advance redevelopment proposals. While the Los Angeles River Master Plan, released in 2022, outlines a comprehensive framework for revitalizing the river and its adjacent areas, significant progress on the Piggyback Yard transformation has been limited due to the property’s continued use as a rail yard.

- Wildpath & The Florida Wildlife Corridor: Wildpath has played a pivotal role in the conservation of millions of acres within The Florida Wildlife Corridor. Their work in raising awareness and advocating for land protection has led to significant legislative action, ensuring the long-term preservation of critical habitats. Their Emmy-winning documentary, Path of the Panther, has brought national attention to the urgent need for conservation efforts.

- Bogotá, Colombia: Eastern Hills Ecological and Recreational Corridor: This ambitious project, led by environmental planner Diana Wiesner, integrates natural ecosystems with recreational spaces to promote sustainability and urban resilience.

- London Green Spaces: The Map of London Green Spaces, produced by Greenspace Information for Greater London (GiGL), highlights the city’s extensive green infrastructure, demonstrating a successful model for urban green corridor integration.

Policy & Place

Aligning policy with green corridors for placemaking requires a multi-layered approach that integrates land-use planning, environmental protection, community engagement, and sustainable development. Here’s how policymakers can support green corridor initiatives:

1. Incorporate Green Corridors into Urban and Regional Plans

- Mandate the inclusion of green infrastructure in zoning laws and urban development plans.

- Require ecological impact assessments for new developments to protect and integrate existing corridors.

- Promote mixed-use developments that incorporate green spaces and connectivity.

2. Strengthen Environmental Protections

- Establish protected status for green corridors through conservation easements or municipal land designations.

- Enforce buffer zones around critical habitats to prevent encroachment from urban expansion.

- Implement wildlife-friendly infrastructure regulations, such as green bridges and underpasses.

3. Incentivize Private Sector & Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

- Offer tax credits or development incentives for projects that enhance green corridors.

- Create green bonds or funding mechanisms to support conservation and restoration efforts.

- Encourage real estate developers to integrate nature-based solutions in exchange for zoning benefits.

4. Enhance Mobility & Accessibility

- Align transportation policies with pedestrian and cycling networks to reduce car dependency.

- Invest in multi-modal transit systems that complement green corridors (e.g., The Underline in Miami).

- Implement greenway standards in infrastructure projects to ensure public access and safety.

5. Foster Community Stewardship & Engagement

- Support community-led conservation initiatives through grants and participatory planning.

- Create educational programs to increase awareness of green corridor benefits.

- Encourage local businesses to sponsor green corridor maintenance and public programming.

6. Integrate Climate Resilience Policies

- Align green corridors with stormwater management and flood mitigation strategies.

- Use native plant policies to support biodiversity and reduce maintenance costs.

- Implement carbon sequestration goals through afforestation and rewilding projects.

Go Green

Green corridors are not just environmental features; they are lifelines for ecosystems and urban communities alike. By investing in these natural pathways and supporting organizations dedicated to their preservation, we can create cities that are not only sustainable but also more livable and connected. As we envision the future of urban and regional planning, green corridors should be at the heart of our efforts to harmonize development with nature.

With the Future of Cities expansion to Europe, we’ve been keeping our finger on the pulse for innovative conservation efforts, particularly in Portugal.

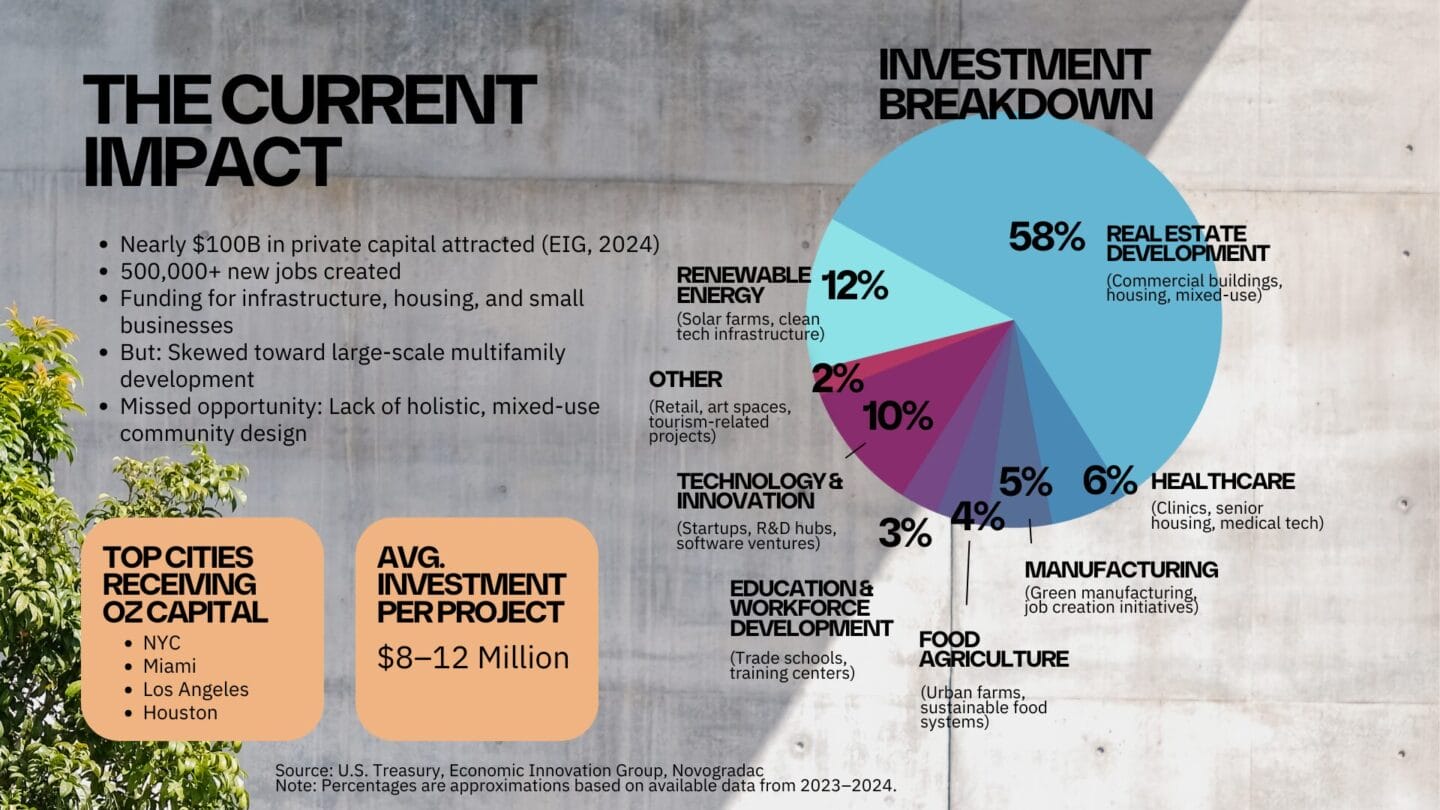

Initiatives like the Azores Marine Protected Area exemplify the critical intersection of biodiversity preservation, sustainable economic opportunity and cultural well-being. This new legislation, announced in October 2024 leading up to the UN Biodiversity Conference (CBD COP16) in Cali, Colombia, establishes the largest marine protected area network in the North Atlantic Ocean.

“The sea is an integral part of our collective identity, being vital socially, culturally and economically. We are committed to protect and recover our ocean to support a healthy blue economy. Our decision through a science-based and participatory process leading to the protection of 30% of our seas serves as an example that other regions must follow now to ensure the future health of the planet.”

José Manuel Bolieiro, President of the Regional Government of the Azores.

A Milestone for Ocean Protection

Spanning 287,000 square kilometers (about 110,800 square miles), the Azores’ new marine protected area (MPA) safeguards 30% of the surrounding ocean. This effort aligns with the global goal set in 2022 to protect 30% of the world’s land and ocean by 2030—a target aimed at addressing the urgent biodiversity crisis. Currently, only 8% of the ocean is under protection, and less than 3% is fully or highly safeguarded, making the Azores’ achievement a monumental step forward.

The Azores’ marine conservation effort isn’t just about numbers; it’s a testament to science-driven and participatory governance. The Azores Archipelago began their efforts with marine protection in the 1980s, evolving through joint collaboration among government, universities, and local communities. The Blue Azores program, launched in 2019 from a partnership between the Regional Government of the Azores, the Oceano Azul Foundation and the Waitt Institute, and the University of the Azores, has contributed to significant advances in marine conservation in the region.

“The benefits from this Marine Protected Area network will be far-reaching across Europe, North America and North Africa,”

says Bernardo Brito E Abreu, who’s been leading the Blue Azores team and is the Advisor to the President of the Government of the Azores on Sea Affairs and Fisheries.

This process ensures the preservation of deep-sea corals, whales, dolphins, sharks, manta rays, unique hydrothermal vent ecosystems, and countless other marine species as MPAs are widely recognized as the most effective tool in the global effort to reverse biodiversity loss.

The Azores is an autonomous region off the coast of Portugal, consisting of a stunning archipelago of nine volcanic islands in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located about 1,360 kilometers (850 miles) west of mainland Portugal, the Azores are renowned for their breathtaking natural landscapes, rich marine biodiversity, and unique cultural heritage.

- Geography and Nature:

- The islands are volcanic in origin, featuring dramatic cliffs, lush green valleys, crater lakes, hot springs, and rugged coastlines.

- The archipelago includes nine islands divided into three groups:

- Eastern Group: São Miguel and Santa Maria

- Central Group: Terceira, Graciosa, São Jorge, Pico, and Faial

- Western Group: Flores and Corvo

- Marine Biodiversity:

- The waters surrounding the Azores are a hotspot for marine life, including whales, dolphins, sharks, manta rays, and deep-sea corals.

- The region is particularly known for whale watching and as a migratory route for various marine species.

- Culture and Autonomy:

- The Azores have a distinct cultural identity, shaped by centuries of Portuguese heritage combined with the isolated geography of the islands.

- The islands operate as an autonomous region of Portugal with their own government, legislative assembly, and administrative policies.

- Sustainability and Conservation:

- The Azores are globally recognized for their commitment to environmental conservation and sustainable tourism.

- Recent initiatives, such as the creation of the Azores Marine Protected Area Network, underscore the region’s dedication to protecting biodiversity.

The Azores is a prime example of a region balancing environmental conservation with economic development, making it an inspiring model for regenerative living and sustainable tourism.

Why Marine Conservation Matters for Urban Life

What does an oceanic conservation milestone have to do with the health of cities and their residents? The answer lies in the interconnectedness of ecosystems and urban environments. Marine ecosystems are vital to the planet’s climate regulation, carbon sequestration, and food security—all factors that directly or indirectly impact urban populations.

Healthy oceans contribute to civic health by:

- Enhancing Climate Resilience: Coastal and marine ecosystems, like mangroves and coral reefs, act as natural barriers against storms and rising sea levels. Protecting these ecosystems supports urban areas vulnerable to climate-related disasters.

- Ensuring Food Security: Sustainable fishing practices within MPAs ensure long-term food supply chains for urban and rural populations alike.

- Boosting Economic and Cultural Vitality: Coastal cities benefit economically and culturally from marine tourism and sustainable industries tied to vibrant ocean ecosystems.

The Azores as a Model for Autonomy & Sustainability

The Azores’ achievement serves as a model for how science-based, community-driven initiatives can lead to sustainable growth. By prioritizing conservation, the region not only protects biodiversity but also sets a precedent for urban areas to integrate nature-based solutions into their development plans.

The work of organizations like Pristine Seas, which has contributed to 29 marine protected areas globally, showcases the importance of partnerships in achieving such ambitious goals. For urban planners, policymakers, and environmental advocates, the Azores’ success underscores the value of cross-sector collaboration in tackling the interconnected challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, and civic well-being.

Together, we can co-create a future where land and ocean conservation are deeply intertwined with the health and vitality of urban communities.

Join Us in Portugal

Sources:

- National Geographic: The Azores Establishes Largest Marine Protected Area Network in Europe

- National Geographic Expeditions: Exploring Portugal and the Azores

- https://iucn-members.us/2024/11/08/azores-archipelago-become-north-atlantics-largest-mpa/

- https://www.discoverwildlife.com/environment/azores-marine-protected-area

A Conversation with Scott Francisco on a new NY State Bill & tropical deforestation

Regenerative Placemaking Demonstration Series

by: Alexandra J Tohme

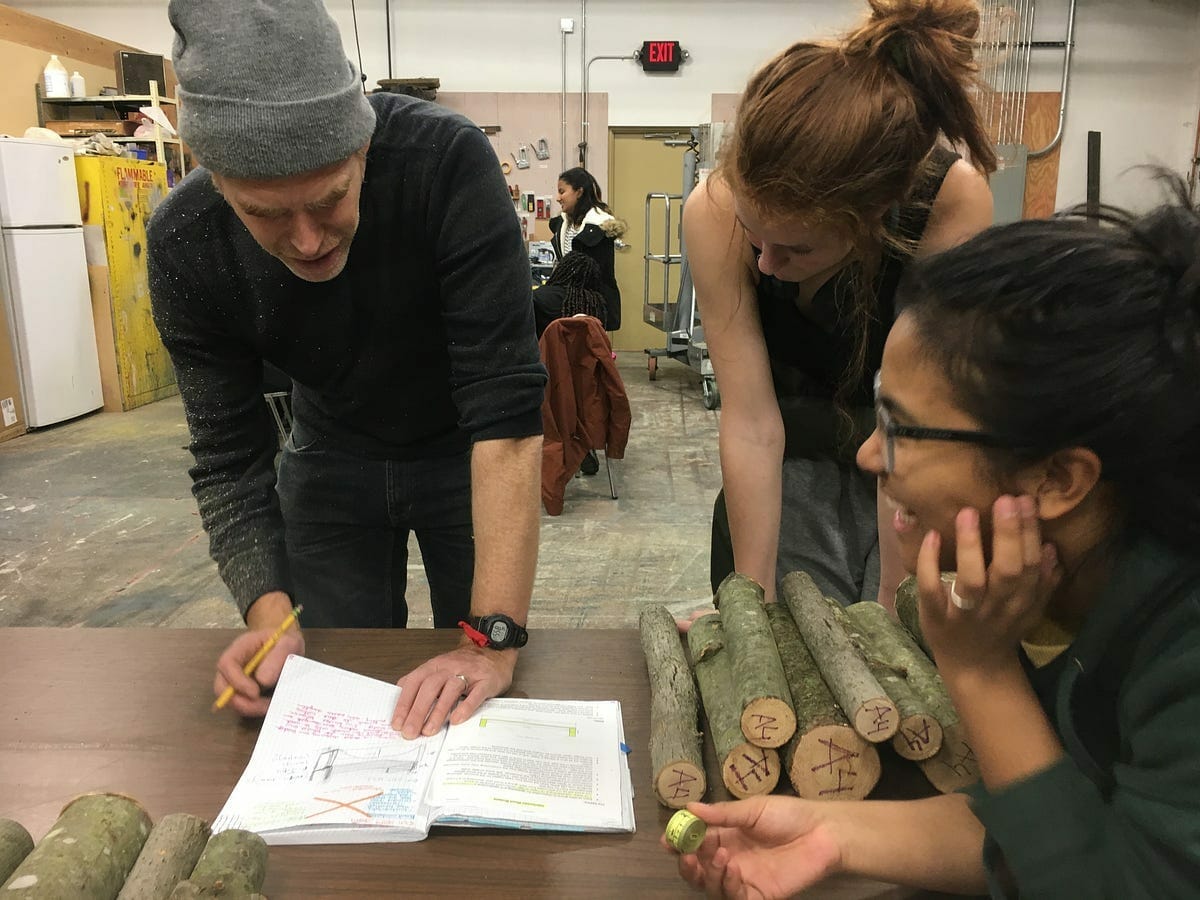

As the world faces complex environmental challenges so interlinked to production and consumption, the conversation around deforestation has gained significant momentum. Future of Cities sat down with Scott Francisco, the founder and director of Pilot Projects Collaborative and co-founder of Cities4Forests, to discuss the New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act, the main causes of deforestation, our consumer choices, and how cities can actively engage with forests and forest communities for a regenerative future.

Our conversations began in Switzerland, at a small conference called the Klosters Forum that brought together built environment practitioners, designers, architects and academics in a collaborative setting high up in the mountains outside of Zurich.

As Future of Cities connected with new strategic partners, I decided to follow up on a post that caught my attention on Scott’s LinkedIn, about the New York Bill S 4859.

Interviewing Scott gave me insight into a fascinating market and unique global network connecting indigenous and local family-run forest harvesting communities — to major cities. From Guatemala to Gabon, Mexico and the US — there are regenerative practices being implemented to offer timber as a low-carbon substitute for construction and architecture, while supporting the biodiversity and forest restoration of tropical landscapes.

The discussion in this article seeks to bring light to the cross-sector cutting issue of tropical forests — of prominent importance to demonstrate innovative solutions that hit many positive outcomes for people and the planet.

Long-term relationships are being built across borders and continents — connecting rainforest communities with scientists, architects and city-planners. We hope the new New York State Bill takes this into account.

Scott Francisco’s 30+ year career and passion for Wood and Forests

Scott Francisco introduced himself as an architect with a deep passion for wood as a construction material. He remembers how his undergraduate thesis involved creating an all- plywood house, a concept seeming bizarre at the time in the 1990s but foreshadowing the current excitement for mass timber buildings.

His love for wood led him to consider the larger role of forests in urban development: Can we use wood as a low carbon substitute for concrete and steel, and at the same time protect larger areas of forest from deforestation? Think of a park bench or office building made of wood, instead of concrete, and the forest supplying the timber given a secure future as a result. This opens many possibilities for other architecture & construction using wood to become investors in the future of forests and cities.

He co-founded Cities4Forests, a global network of cities working towards integrating forests into their climate action plans.

The New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act: Explained

Francisco dove into the New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act, a bill aimed at curbing deforestation’s negative impacts. The bill prohibits government procurement contracts from including any products associated with deforestation. However, there was a crucial issue — the bill treated all tropical timber equally, regardless of its source or regenerative practices. Poor timber management practices, including illegal and high intensity logging and some monoculture industrial timber plantations, do drive deforestation in many tropical forests. But it’s not the whole story.

“The main drivers of deforestation are the industrial-scale production of beef, soy and palm oil,” said Francisco, primarily in tropical regions, highlighting the growing global commodity and demand for palm oil over the past 15 years, which has resulted in large areas deforested in Indonesia. Beef and soy are similarly destructive in the Amazon.

We at Future of Cities are big advocates and practitioners of biodiverse, small-scale family farming, social forestry, regenerative soil agriculture. The way in which we grow our products and crops deeply affects so many other areas of our lives, health and the planet.

Conservation Timber: A Sustainable Alternative by Local Communities

Scott explained the concept of “conservation timber,” wood harvested sustainably in low volumes from community-managed forests. This approach offers local communities an alternative to deforestation while ensuring biodiversity conservation.

As we focus on regenerative placemaking solutions at FOC — it is so powerful to learn about these methods that allow the forest to regenerate, through active community engagement.

Recognizing and promoting conservation timber and other forest products by local communities is critical for healthy ecologies and economies.

Thousands of families rely on a sustainable harvest of timber as their primary livelihood, to support their children and communities. It didn’t seem right or logical to draft a bill that blanket-prohibits all kinds of timber in government contracts regardless of whether or not they are good for the communities and the forest, or what the outcomes will be.

He suggested an amendment to the Bill that specifically states criteria based on management practices that maintain healthy biodiversity, and are economically productive so that those same communities have an alternative to having their forest completely cut down.

One example of such a definition for this criteria could be Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification, the broadest and most robust global certification program for timber. FSC certified timber could be a requirement that is added and adjusted in this Bill.

He emphasizes that we can look at timber harvest the same way you would for chocolate or coffee production — two wonderful commodities that also come from tropical forests. There are two ways to harvest: clearcut monoculture that destroys biodiversity and nature-based livelihoods, or regenerative models that rely on shade and rich biodiversity and therefore keep forest landscapes intact.

Imagine if the State of New York decided to purchase only shade-grown bird friendly coffee for government employees that comes from these biodiverse landscapes?

“Just like coffee can be terrible or wonderful for a forest landscape, so can timber be terrible or wonderful.” Francisco said, his passion clear throughout his thoughtful analyses.

Advocacy at NYC Climate Week + A Guidebook for Developers

“So what can we do?” I inquired, asking about the tools for advocacy and awareness to protect these indigenous-model systems of local and regenerative forestation for construction and urban development. While this bill is still sitting with the governor, he encourages people to engage in constructive discussion and connect to government representatives, notably with NYC Climate Week coming up next week. He encourages engagement with his LinkedIn post, welcoming comments, revisions and feedback to the points he outlined in a letter to the Governor.

Francisco has also co-created useful tools such as the Forest Footprint for Cities, which helps cities track their tropical forest (and climate) impact, and invites us all to check on our cities and use data tools like this in our work, education, and policy advocacy.

Pilot Projects has developed a Sustainable Wood for Cities — a detailed guide for city governments, and private sector group (architects, engineers, developers) to evaluate the sustainability of their wood options, the source and production process, “we call them pathways that can guide you towards higher level of sustainability in your wood choice.”

It’s free to use and anyone can access it at citywoodguide.com

Francisco and I ended the conversation recognizing the value of activating a positive relationship between the rural and urban landscapes to mutually support each other:

“We have to activate cities to be proactive with their rural counterparts.”

To conclude with an excerpt from Scott Francisco’s message:

“Time, science (and satellite photos!) have clearly shown that management by local community residents is the best way to ensure that these forests are intact and healthy decades and centuries later. The businesses that these communities create keep the brightest, most dedicated young people working in these forests, and allows for generational knowledge-transfer over the long term.”

Major conservation organizations like Wildlife Conservation Society, Rainforest Alliance, World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, U.S. Forest Service, USAID, The Nature Conservancy, and hundreds more, support community-led conservation timber enterprises.

We hope that the great State of New York will too.

Join the regenerative placemaking movement: Subscribe to our newsletter at focities.com to get involved, email me at: ajtohme@focities.com and follow us on Instagram.

Get in touch with Scott Francisco: scott@pilot-projects.org to learn more about tropical forests and forest communities around the world and follow @partnerforestprogram and @cities4forests.