With thanks to conversations with Ludo Campbell-Reid, Ralph Webster,

and Frith Walker

Twenty years ago, the City of Auckland was suffering from a depressed economy, declining public health, and a short-term, self-centric viewpoint called “Auckland disease.” Now a decade later with a ten-fold increase in private investment, public transport patronage doubling every year, and the strengthening of its social and natural systems, Auckland’s embrace of Regenerative Placemaking principles has resulted in this remarkable transformation and the recent recognition as the most liveable city in the world.

Employing regenerative thinking in the sense of re-activating and enlivening the city; using the city to support social and ecological capacity; and activating these strategies through fine-grained testing of ideas and active agency of stakeholders; Auckland’s efforts to revitalize the heart of the city have been extraordinary.

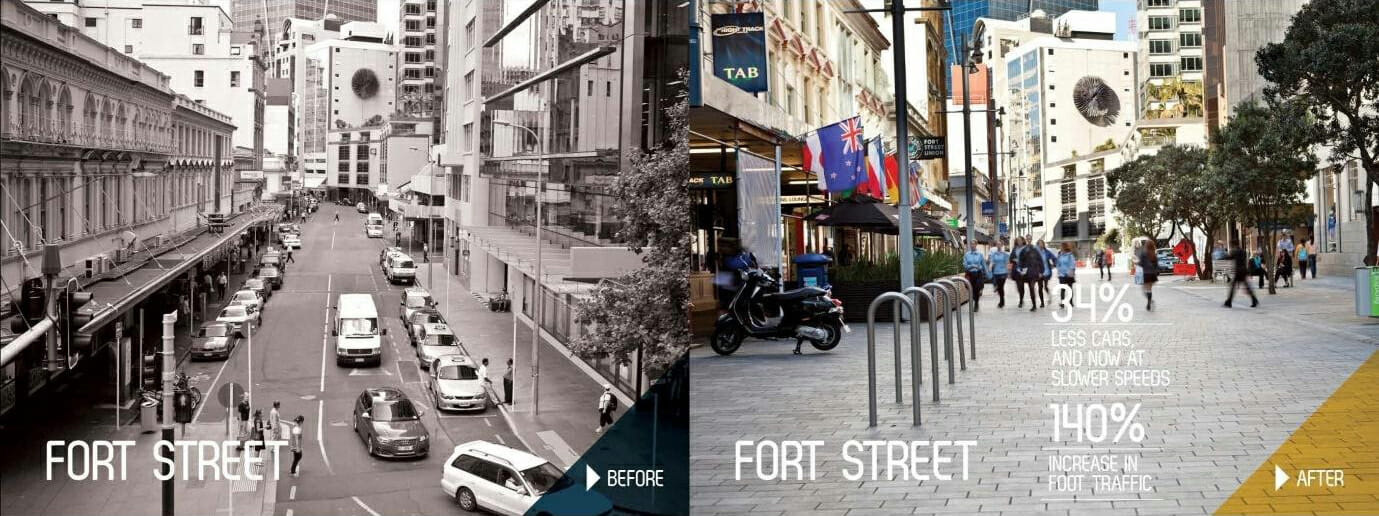

For example, take the transformation of Fort and Elliott Streets. On Fort Street, there has been a 54% increase in pedestrian volumes and a 47% increase in consumer spending, while on Elliott Street there has been a 10% pedestrian and 27% spending increase.

However, while these are tangible examples in simple terms, there are many additional reflections to map Regenerative Placemaking components over the past decade in Auckland. Six of note are:

- Living systems thinking

Understood as a philosophy that studies the interrelation and dependence of all stakeholders and environments in a given place, for Auckland this approach was leveraged to emphasize reconnecting to its natural systems – the bay, rivers, and mountains.

In practice, this was realized by:

- The rebuilding of a plaza – cantilevered over the water to improve its ability to withstand earthquakes – as a mussel habitat that helped clean the water and improve the eco-system

- The redevelopment of a vibrant waterfront not with a “anchor tenant” to drive commerce but an “anchor playground” to foster community and children’s health

- The integration of public transport connections within privately financed projects to encourage health transport, reducing the reliance and negative impact of cars

- The repurposing of a discussed offramp into the Nelson Street Cycleway known as Te Ara I Whiti (“Pink Path”). Inspired by the Highline in New York City, this Pink Path has an LED mood lighting system that constantly changes the Māori name

- Transdisciplinary knowledge exchange

Focused on consulting with everyone to gain significant ideas and better solutions, Ralph Webster, the Auckland Council’s former program development manager said that working on a Regenerative Placemaking development was not “just a team sport, but an intergenerational team sport.”

How so?

- Diversifying decision making and being inclusive of indigenous populations, the Auckland Council appointed a Māori Design Leader resulting in greater custodianship and integration of the Māori language and worldview in all activities

- A governance structure that functioned like a fractal or mycelian network of engagement and responsibility, meaning decisions flowed from the smallest communities to the highest levels of decision making and back down again

- Rigorous and inclusive community engagement

Community engagement done well means that they are agents in the eventual outcome and have a sense of custodianship and stewardship which is critical. This creates attachment and belonging leading to positive social, ecological, and economic outcomes.

Critically this engagement should not only be about extracting ideas and good will from participants it is ensuring they gain benefit from the experience also as Webster said, “In addition to working with all stakeholders in projects to increase the vitality and vibrancy of a place, one of the most critical parts is to create the potential to have fun, laugh and play through the process and embed it in the end result.”

In Auckland this came to life in practical terms by:

- Speaking to all stakeholders with the intent to learn something: from children to entrepreneurs, homeless to shop keepers. And remember, nature is a stakeholder too

- Connect into the Indigenous worldview

- Listen, do, learn, do, listen, do, learn, do – evaluate and reflect, and then repeat to measure the implication and drive success

- Biophilia and sustainability practices

Throughout Auckland, connection to nature is an integral part of how spaces are looked at, from working with threatened species to how to plan support biodiversity. This is evidenced through experimentation with green roofs on shipping container activation nodes, using them for insects and other small threatened species.

Auckland’s focus on nature enables them to imagine future potential, and this leads to human benefits such as reduced urban heat and biophilic benefits with a stronger connection to nature.

These practices are put into action by asking these simple questions:

- How can ecological value be added?

- How can we connected ecosystems around us to interact, learn and contribute?

- How can we realize and communicate the social and economic benefits of creating a nature- filled place?

- Regenerative placemaking interventions

Testing within the community was an integral part of the City of Auckland’s processes and their work with stakeholders. Practically, this collaboration has resulted in the Activate Auckland plan to support the 30-year strategic redevelopment plan of the City.

- Avoiding gentrification

Auckland has attracted its share of critique for increased housing prices, yet this was addressed by creating innovative models to support home ownership and community planning.

For example:

- Collaboration across agencies and community on urban innovative home ownership models Shared ownership (SO) is a policy alternative widens access to affordable housing to low and moderate-income households by allowing the potential owner to purchase a share in a property (between 20-80%), while a third party (e.g., a housing association) owns the remaining share, on which the shared owner pays rent.

- On the waterfront, rather than displacing existing businesses, fish markets were made central to the ongoing development. This allowed local workers to stay employed and protected these businesses.

Conclusion

While Regenerative Placemaking is an ever-evolving, living development approach, Auckland demonstrates through its transformation as one of the least to most-liveable cities that with incredible amounts of private investment, collaboration, preservation, and conservation that a socially, ecologically, and socially thriving city can be willed. All it takes is commitment and vision!

Introduction by Tony Cho, Future of Cities Founder

This past year has been one of deep global transformation as we continue to navigate through one of the most impactful events in modern human history. The global pandemic has revealed a tale of two worlds, the haves and have-nots. The social and racial inequality gap continues to dramatically widen, and people and governments around the world are reevaluating policies, searching for answers and figuring out what’s next. How do we build back better, more sustainably, more equitably and more inclusively so 100% of humanity can thrive — while remaining in balance with nature?

This inquiry is at the core of our mission at the Future of Cities, where we aspire to impact the lives of 1 billion people through innovations in the built environment. So, how do we do this and where do we begin? Over the past 3 years, we’ve studied and analyzed Systems-Thinking theories ranging from Buckminster Fuller to the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and recognized a need to co-design a new systems-oriented framework for real estate development. This framework we aim to open-source and share widely, putting forward new standards that will be embodied in demonstration projects that can serve as beacons for those interested in new, regenerative pathways for urban development and vitality.

Building on local learnings from creative placemaking derived over the past two decades developing Miami’s Wynwood Art’s District and Magic City Innovation District in Little Haiti, combined with Regenerative Development practices most notably proposed by Bill Reed and Pamela Mang’s team at Regenesis, we’ve set out to co-create and popularize a new framework, entitled Regenerative Placemaking, which aims to accelerate place-based sustainability into new, mainstream industry norms.

In this process of discovery, we were quickly directed to Dr. Dominque Hes, one of the world’s foremost thinkers, theorists and practitioners of Regenerative Placemaking. Dr. Hes has been formulating the Regenerative Placemaking theory for several years and has authored multiple articles on the topic.

We are grateful and honored to welcome Dr. Hes to our global board of advisors for the Future of Cities, and excited to co-create, design and open-source our research on this critical advancement for our industry. The time has never been more urgent for developers to reimagine their role as stewards who are responsible for the wellbeing of communities and cities. And so, we are pleased to introduce you to this newly synthesized and still-emergent body of work, with hope you will be inspired to build the future with these values in motion, to evolve the role of placemaking, and urban development as we know it.

Creating The Future of Cities With Regenerative Placemaking

By Dr. Dominique Hes, Advisor to Future of Cities, with Bill Reed of Regenesis

Addressing Systemic Failures

The world’s urban population is playing a game of chicken with our environment and global economy. By 2050, more than 6.6 billion people, or 68.4 percent of the population, will live in cities. However, whether the threat of pandemic, sea level rise, food deserts, or myriad of other challenges, this growth is going unchecked.

Does this mean a moratorium should be placed on urban density in favor of suburban sprawl? Or is a solution that is more evolutionary and redefines urban living and development more feasible?

The answer is that we must create places that support the future of cities. Places designed for living, working, creating, and contributing, combined with strategies that incorporate nature integration and the non-human aspects of life critical to all local ecosystems. Enter, regenerative placemaking.

Enter: A New Design Paradigm

Defined as a strategic process of (re)igniting people’s relationship to socio-ecological systems through place-specific activations, regenerative placemaking harnesses the key strengths of regenerative development and placemaking practices.

The merging of these two practices delivers places designed for both humans and non-humans, shifting city-making from a largely anthropocentric practice to one aligned with living systems, by which people are empowered as cultural and environmental stewards.

The result is the creation of a way to interact with a geographical location that enables continual adaptation, health, and wellbeing. The aim is not to create utopia, but a realistic way to engage with the problems and potentials of a place and all its complexities.

The regenerative development component creates the ways to understand a place, to see its essence, its potential and the ways to understand what healthy, vital, viable and abundant looks like. The placemaking component ties these ideas to a specific place, with the local stakeholders, supporting them to be a critical part of the potential of the place and its capabilities.

Pandemic Lessons and Proper Practices

While the effects on populations and economies were severe, what the pandemic showed was how changes in urban living could influence our environment. From better air quality and cleaner water ways to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, the global population can slow and reverse negative climate impacts.

To start creating regenerative placemaking demonstration projects, what is needed is a process to guide design and development, and to enable the ability to learn, understand, and grow. Key components in moving regenerative placemaking forward include:

- Living systems thinking, employed as a way of understanding the socio-ecological aspects of place

- Rigorous and inclusive community engagement to gather the patterns/essence of place, identify the values and needs of the present and past, and deliver an ongoing strategy for engagement at self, group, system actualization levels

- Transdisciplinary research and education, acting as a vehicle for knowledge exchange

- Ecological aesthetic (i.e., biophilia) and sustainability practices, assisting people to visualise a healthier living environment

- Regenerative placemaking interventions (i.e., pop-up parks, festivals), as a way of trialling programming and design ideas for long-term projects and planning initiatives.

Measuring and Refining Success

Having developed the ways to enact the above processes, how does a project understand how well it has done?

The first step is to understand that measurement serves a developmental process, not as a way to ‘score’ an effort. The second step is to evolve and adapt measurement as within regenerative placemaking, fixed and adaptable system measures can change over time in negotiation with stakeholders. We ask: what are the signs of life of a healthy place (fixed) and what are the unique traits of thriving and abundance of the place that may change as it matures (adaptable)?

However, while the measures and benchmarks can shift, the objective does not. Regenerative Placemaking is about contributing to improved social, ecological, and economic outcomes by building local capacity and potential. This means looking at the richness of the relationships – individual, community, built and natural environment – contributing to these outcomes.

Though not a perfect example of the full potential of Regenerative Placemaking, a project that illustrates the importance of building relationships to the flows through a place is the Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project. In this example, water flowing through a community is of no benefit in a pipe where it cannot contribute positively through relationship (habitat, urban cooling, watering, recreation, etc.), similarly, money flowing through a place is only beneficial if it nourishes and contributes to the area. Michael Shuman has shown that every dollar spent at a locally owned business generates two-to-four times the jobs, income, wealth, and taxes as a dollar spent in a comparable nonlocal one (link).

The Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project

Benefits of daylighting the river:

- flood protection for up to a 200-year flood event

- Increased overall biodiversity by 639%

- reduction of urban heat island 3.3° to 5.9°C

- Reduced small-particle air pollution by 35%

- Attracted (pre Covid-19) an average of 64,000 visitors daily and $1.9 million USD) in visitor spending.

- Business growth 1.5% higher than neighboring areas

- Land prices increased 30-50% (though this is also a gentrification danger)

Find more information on the Cheonggyecheon Stream Restoration Project here ⟶ https://www.landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/cheonggyecheon-stream-restoration

Moving Forward

To implement regenerative placemaking principles, a sea change is required in how developers approach projects and their regulation. From the scaling of ESG standards and creating incentives for sustainable development, to further enhancing Opportunity Zone framework and shifting investors’ mindsets to focus beyond triple bottom-line returns, to creating local potential, these adaptations are vital and achievable.

It is the responsibility of those with the ability to influence change to make it happen, and for stakeholders and communities to help co-create the future in support of better, self-sustaining cities.

About Dr. Dominique Hes

Holding a PhD in Architecture and Degree in Engineering from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology and Botany degree from Melbourne University, Hes is an associate of the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute and award-winning author. She is also the chair of the board of Greenfleet, and an advisor for the Future of Cities; a mission-driven consortium that is part-real estate investment and development company, part-venture capital ecosystem and part-think tank that will cultivate living laboratories to steward regeneration and improve liveability in cities.