A Conversation with Scott Francisco on a new NY State Bill & tropical deforestation

Regenerative Placemaking Demonstration Series

by: Alexandra J Tohme

As the world faces complex environmental challenges so interlinked to production and consumption, the conversation around deforestation has gained significant momentum. Future of Cities sat down with Scott Francisco, the founder and director of Pilot Projects Collaborative and co-founder of Cities4Forests, to discuss the New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act, the main causes of deforestation, our consumer choices, and how cities can actively engage with forests and forest communities for a regenerative future.

Our conversations began in Switzerland, at a small conference called the Klosters Forum that brought together built environment practitioners, designers, architects and academics in a collaborative setting high up in the mountains outside of Zurich.

As Future of Cities connected with new strategic partners, I decided to follow up on a post that caught my attention on Scott’s LinkedIn, about the New York Bill S 4859.

Interviewing Scott gave me insight into a fascinating market and unique global network connecting indigenous and local family-run forest harvesting communities — to major cities. From Guatemala to Gabon, Mexico and the US — there are regenerative practices being implemented to offer timber as a low-carbon substitute for construction and architecture, while supporting the biodiversity and forest restoration of tropical landscapes.

The discussion in this article seeks to bring light to the cross-sector cutting issue of tropical forests — of prominent importance to demonstrate innovative solutions that hit many positive outcomes for people and the planet.

Long-term relationships are being built across borders and continents — connecting rainforest communities with scientists, architects and city-planners. We hope the new New York State Bill takes this into account.

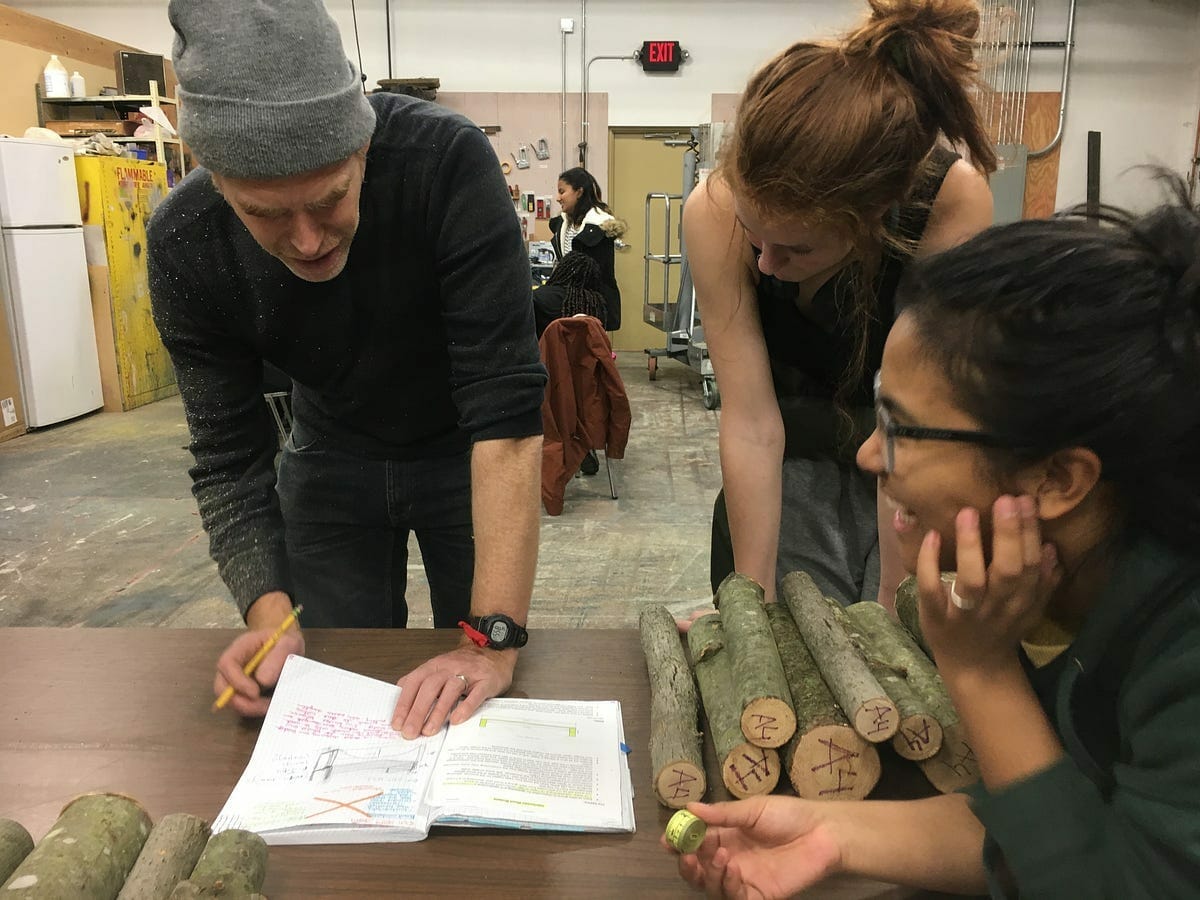

Scott Francisco’s 30+ year career and passion for Wood and Forests

Scott Francisco introduced himself as an architect with a deep passion for wood as a construction material. He remembers how his undergraduate thesis involved creating an all- plywood house, a concept seeming bizarre at the time in the 1990s but foreshadowing the current excitement for mass timber buildings.

His love for wood led him to consider the larger role of forests in urban development: Can we use wood as a low carbon substitute for concrete and steel, and at the same time protect larger areas of forest from deforestation? Think of a park bench or office building made of wood, instead of concrete, and the forest supplying the timber given a secure future as a result. This opens many possibilities for other architecture & construction using wood to become investors in the future of forests and cities.

He co-founded Cities4Forests, a global network of cities working towards integrating forests into their climate action plans.

The New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act: Explained

Francisco dove into the New York State Tropical Deforestation Free Procurement Act, a bill aimed at curbing deforestation’s negative impacts. The bill prohibits government procurement contracts from including any products associated with deforestation. However, there was a crucial issue — the bill treated all tropical timber equally, regardless of its source or regenerative practices. Poor timber management practices, including illegal and high intensity logging and some monoculture industrial timber plantations, do drive deforestation in many tropical forests. But it’s not the whole story.

“The main drivers of deforestation are the industrial-scale production of beef, soy and palm oil,” said Francisco, primarily in tropical regions, highlighting the growing global commodity and demand for palm oil over the past 15 years, which has resulted in large areas deforested in Indonesia. Beef and soy are similarly destructive in the Amazon.

We at Future of Cities are big advocates and practitioners of biodiverse, small-scale family farming, social forestry, regenerative soil agriculture. The way in which we grow our products and crops deeply affects so many other areas of our lives, health and the planet.

Conservation Timber: A Sustainable Alternative by Local Communities

Scott explained the concept of “conservation timber,” wood harvested sustainably in low volumes from community-managed forests. This approach offers local communities an alternative to deforestation while ensuring biodiversity conservation.

As we focus on regenerative placemaking solutions at FOC — it is so powerful to learn about these methods that allow the forest to regenerate, through active community engagement.

Recognizing and promoting conservation timber and other forest products by local communities is critical for healthy ecologies and economies.

Thousands of families rely on a sustainable harvest of timber as their primary livelihood, to support their children and communities. It didn’t seem right or logical to draft a bill that blanket-prohibits all kinds of timber in government contracts regardless of whether or not they are good for the communities and the forest, or what the outcomes will be.

He suggested an amendment to the Bill that specifically states criteria based on management practices that maintain healthy biodiversity, and are economically productive so that those same communities have an alternative to having their forest completely cut down.

One example of such a definition for this criteria could be Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification, the broadest and most robust global certification program for timber. FSC certified timber could be a requirement that is added and adjusted in this Bill.

He emphasizes that we can look at timber harvest the same way you would for chocolate or coffee production — two wonderful commodities that also come from tropical forests. There are two ways to harvest: clearcut monoculture that destroys biodiversity and nature-based livelihoods, or regenerative models that rely on shade and rich biodiversity and therefore keep forest landscapes intact.

Imagine if the State of New York decided to purchase only shade-grown bird friendly coffee for government employees that comes from these biodiverse landscapes?

“Just like coffee can be terrible or wonderful for a forest landscape, so can timber be terrible or wonderful.” Francisco said, his passion clear throughout his thoughtful analyses.

Advocacy at NYC Climate Week + A Guidebook for Developers

“So what can we do?” I inquired, asking about the tools for advocacy and awareness to protect these indigenous-model systems of local and regenerative forestation for construction and urban development. While this bill is still sitting with the governor, he encourages people to engage in constructive discussion and connect to government representatives, notably with NYC Climate Week coming up next week. He encourages engagement with his LinkedIn post, welcoming comments, revisions and feedback to the points he outlined in a letter to the Governor.

Francisco has also co-created useful tools such as the Forest Footprint for Cities, which helps cities track their tropical forest (and climate) impact, and invites us all to check on our cities and use data tools like this in our work, education, and policy advocacy.

Pilot Projects has developed a Sustainable Wood for Cities — a detailed guide for city governments, and private sector group (architects, engineers, developers) to evaluate the sustainability of their wood options, the source and production process, “we call them pathways that can guide you towards higher level of sustainability in your wood choice.”

It’s free to use and anyone can access it at citywoodguide.com

Francisco and I ended the conversation recognizing the value of activating a positive relationship between the rural and urban landscapes to mutually support each other:

“We have to activate cities to be proactive with their rural counterparts.”

To conclude with an excerpt from Scott Francisco’s message:

“Time, science (and satellite photos!) have clearly shown that management by local community residents is the best way to ensure that these forests are intact and healthy decades and centuries later. The businesses that these communities create keep the brightest, most dedicated young people working in these forests, and allows for generational knowledge-transfer over the long term.”

Major conservation organizations like Wildlife Conservation Society, Rainforest Alliance, World Wildlife Fund, Conservation International, U.S. Forest Service, USAID, The Nature Conservancy, and hundreds more, support community-led conservation timber enterprises.

We hope that the great State of New York will too.

Join the regenerative placemaking movement: Subscribe to our newsletter at focities.com to get involved, email me at: ajtohme@focities.com and follow us on Instagram.

Get in touch with Scott Francisco: scott@pilot-projects.org to learn more about tropical forests and forest communities around the world and follow @partnerforestprogram and @cities4forests.

Shaping America’s Role in the Post-COVID World

On March 4th, 2022, Future of Cities participated in the annual digitally mediated Horasis USA meeting. The meeting focused on the United States’ future and how it impacts the rest of the world. With 750 speakers and more than 150 sessions, it was an insightful event that resulted in numerous proposed ideas to positively shape the future of our world.

Tony Cho, CEO and founder of Future of Cities, was on a panel centered around the complexities of new urbanization—chaired by Timothy J. Nichol of Liverpool John Moores University—with Antonio Cantalapiedra of Woonivers, Mayor Eugene W. Grant of Seat Pleasant, Maxim Kiselev of Skoltech, and Avi Rabinovitch of Creative Links.

About Horasis: Horasis is a “global visions community committed to inspiring our future” and offers leaders and companies a platform to go global.

For more content like this, subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media!

As extreme weather events, like sea-level rise, wildfires, and other ecological disasters occur, climate change is becoming a more real and imminent threat by the day. In response, innovative concepts are spawning to mitigate effects and protect our society’s future. One such approach discussed in the sustainability and climate discourse has been regenerative placemaking. But what is this?

Regenerative placemaking offers a new, holistic approach that is actively being applied in cities on a global scale. It seeks to go beyond net-zero to create a net positive impact on the environment. The principles that support regenerative placemaking are many, including living systems thinking, biophilia, sustainable practices, and community engagement.

In this article, we are highlighting a few cities that are practicing these principles, and what can be learned from them.

1. Copenhagen, Denmark

Already known as the world’s greenest and most habitable city, Copenhagen has employed numerous regenerative placemaking tactics that contribute to its healthy living environment.

- Inclusive Public Spaces: Copenhagen has designed numerous urban development projects to create places that are healthy, sustainable, and foster inclusive social interactions. Sønder Boulevard Street in the Vesterbro neighborhood is one example. With a portion of the Boulevard developed into a recreational park, the green space helps reduce the urban heat island effect, the desired goal in Copenhagen. The park also encourages more walking and more outdoor activities which contribute to the overall health of the community.

- Energy Efficiency: The public’s support for wind power has grown substantially due to the encouragement of community-owned facilities and awareness campaigns. Based on Copenhagen’s Climate Plan, a hundred new wind turbines will be installed by 2025 to contribute to the intermittent energy already being provided from existing wind farms. Their energy efficiency extends to their built environment as well. For instance, a percentage of hotels in Copenhagen have an eco-certificate or other prestigious environmental credentials, through the help of environmental managers.

2. Medellin, Colombia

Medellin is a member of the “100 Resilient Cities” and part of the UN’s Green Cities initiative. In the midst of its natural forests, Medellin is evolving and has proven itself to be a model of social and urban transformation. The city owes its development to the collective co-creation amongst its citizens, public and private organizations. The presence of this transdisciplinary interaction has led to increased levels of community engagement. Emerging from this partnership is an image of a resilient Medellin, one with goals of safety, equity, and sustainability.

- Referred to as the ‘Corredores Verdes,’ Medellin’s Green Corridor initiative was designed to interconnect 30 green corridors within the city that has a host of widespread benefits. The corridors go beyond heat reduction, by improving biodiversity (serving as a home to new ecosystems), sequestering carbon dioxide emissions, and reducing air pollution.

- Sustainable Transportation: The city has the largest electric fleet in Colombia. Vehicles, like electric trams and cable cars, create sustainable connections all over the city, including between impoverished areas and the city centers. Medellin is aiming to be an eco-city and initiatives like these gear it closer to the goal. The city was also awarded the sustainable transport award by the UN.

3. Auckland, New Zealand

As one of the most liveable cities in the world, Auckland continues to find ways to create exceptional strategies that result in the city’s transformation. There is an emphasis placed on eco-design and energy efficiency. For example, the city provides readily available resources to assist the community to make smart choices and reduce waste–whether home or business. Unique to Auckland is its reconnection with its indigenous population and natural systems. In an effort to create diverse and inclusive community engagement, a Māori design leader, Phil Wohongi, was appointed in an aim to foster the integration of identity and culture in Auckland. The city’s outreach includes speaking and listening to various community members and taking action. In regards to natural systems, Auckland has taken up many projects that include the redevelopment of waterfronts and biophilic practices.

- Organic Link at Te Wananga, in Waitematā Harbor: A ferry basin area at Waitematā, suffers from polluted waters. The Auckland Council created a unique natural solution to this issue through the addition of ropes of mussels to the underside of the public outdoor space. Mussels are known to be capable of removing pollutants and are exceptional at filtering seawater. The project illustrates solutions that can be implemented from Māori practices.

- Te Auaunga Awa Restoration (Biophilia in Auckland): it is common to find varying levels of biophilia in Auckland in an effort to increase biodiversity and stormwater management, ranging from green roofs to natural parks. The Te Auaunga Awa (Oakley Creek) project was an upgrade for better flooding and stormwater management. It involved the naturalization of the previous concrete-lined waterway. The upgrades have led to a lush park with a meandering stream and an increase in social, healthy interaction at the Creek.

4. Montevideo, Uruguay

Montevideo is the cultural, political, and economic center of Uruguay. The city is committed to the welfare of its citizens by placing an emphasis on human rights and sustainability. Montevideo is actively implementing the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 agenda. The city has developed a number of strategic plans for development and tackling social, economic, and environmental vulnerability. In 2016, Montevideo was listed as a member of the 100 Resilient Cities Network. A Resilience Executive Unit was established then, to create and deliver a Resilience Strategy by 2018. The Strategy involved regenerative placemaking approaches like inclusivity, co-creation environmental commitments. Beyond this, Montevideo, and Uruguay as a whole, have taken up other projects to constantly improve agricultural and energy systems.

- Renewable Energy: Uruguay is one of the leading countries in renewable energy and is making exceptional headway to be carbon neutral by 2030. 98% of the country’s power is from renewable sources. The Country has also found ways to utilize the biomass produced from agricultural industries to generate electricity.

- Agricultural Systems: The Country has also found effective ways to conserve the natural forests, habitats, and biodiversity. There has also been an integration of smart technologies into the agricultural systems making it possible for “agro-intelligent” agriculture in Uruguay.

Ultimately, what we can learn from these identified cities are the huge role nature, technology, and the community plays. The effectiveness of natural solutions to environmental challenges is evident. We can look to nature as an energy resource, and utilize its cooling and filtration properties. There is also the benefit of equipping the built environment with smart tools for energy measurement and efficiency. All these tactics depend on community engagement. It is important for the community, not just to understand these principles, but also to be involved in them, so that implementation and necessary lifestyle changes will be welcomed.

There are many other cities that are implementing regenerative placemaking principles in an effort to create healthy and sustainable environments; It is only a matter of time before we start seeing the effect of these changes.

For more content like this, subscribe to our newsletter and follow us on social media!